I never really liked math, but of all the subject areas of mathematics I guess I disliked geometry the least. If nothing else, geometry gave me permission to doodle in class and  call it “note-taking.” Needless to say, I am no expert on geometry or on another aspect of mathematics.

call it “note-taking.” Needless to say, I am no expert on geometry or on another aspect of mathematics.

Thankfully, then, “sphere sovereignty” has (virtually) nothing to do with the sphere’s dominance over other geometric shapes such as hexagons or equilateral triangles.

Richard Mouw, in his recent book Abraham Kuyper: A Short and Personal Introduction, reflects on some of Abraham Kuyper’s key contributions to Christian theology and cultural engagement. One of the most helpful concepts in terms of understanding Christianity’s interaction with culture is what Kuyper called “sphere sovereignty.”

The basic questions that Kuyper was seeking to answer is: “Who is in control over [insert any area (sphere) of life: family, church, politics, art, entertainment, education, etc.] and how does that person or thing exercise that control?

Mouw, in summarizing Kuyper’s thinking, identifies two traditional ways of answering that question. The first is what Mouw calls a “church-controlled” answer. The second is a “secularist” answer. The church-controlled option says that God is in control of all areas (spheres) of life, but he exercises that control through the power of the church. Thus all areas of life are governed or directed by the church.

The secularist objects, however. The secularists asserts that God – if there is a God – may have his control over the church, but the other spheres of life (arts, politics, entertainment) are free from his control – and the churches!

In typical Mouwian style, he notes that both the church-controlled and the secularist answers got something right and got something wrong. Mouw writes:

For Kuyper, each of these two models embodied both a positive insight and a fundamental error. The medieval perspective [the church-controlled view] rightly saw that God’s rule must be acknowledged over all spheres of human activity. Its mistake was investing the church with the power to mediate that rule. … The secularist perspective rightly wants to liberate these spheres from the church’s control. Where it goes wrong is in its insistence that to do so is also to take them out from under the rule of God. (40-41)

The church-controlled approach is right in insisting that God is in control over all of life; the secularist is right in insisting that the church is not the right overseer of that control. A better way, suggests Kuyper, is that God directly exercise his authority over each sphere. “Every square inch” of the world – politics and sports, art and science, church and yes, even geometry – lives “coram deo, before the face of God.”

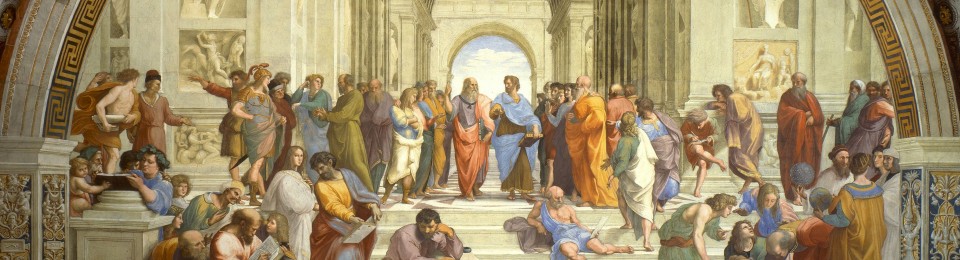

Using an illustration (as close to geometry as I get these days!), sphere sovereignty looks something like this:

Christ is Lord over all of creation and yet there is a “separation of powers.” The church is to submit herself to the Lordship of Christ in a way appropriate to its sphere. Likewise, an economist is to submit herself to the Lordship of Christ and do economics coram deo – before the face of God. Yes, even a protester among the throngs of the Occupy Wall Street movement is to protest coram deo.

Kuyper’s doctrine of “sphere sovereignty” is a true gift to the church. However, as Mouw notes, there are still some unanswered questions. What happens when families fall apart? Is it appropriate for another “sphere” to step in? If so, which one? What role, if any, does the church have of being a prophetic voice to those in politics to enact just laws or to economists to seek fairness and equity? These are tough questions, but Kuyper gives us a helpful starting point to keep thinking about these issues.